‘Fifty years have passed since then, my child,

and change has marked the face of all things.’

– Domicilium, Thomas Hardy

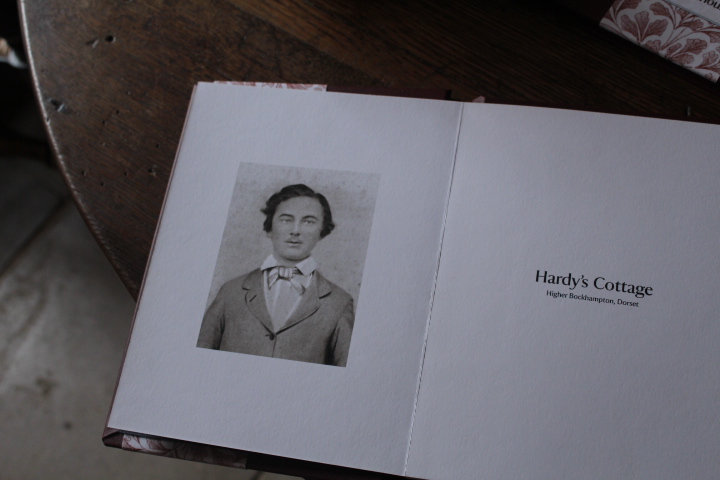

To Hardy’s Cottage

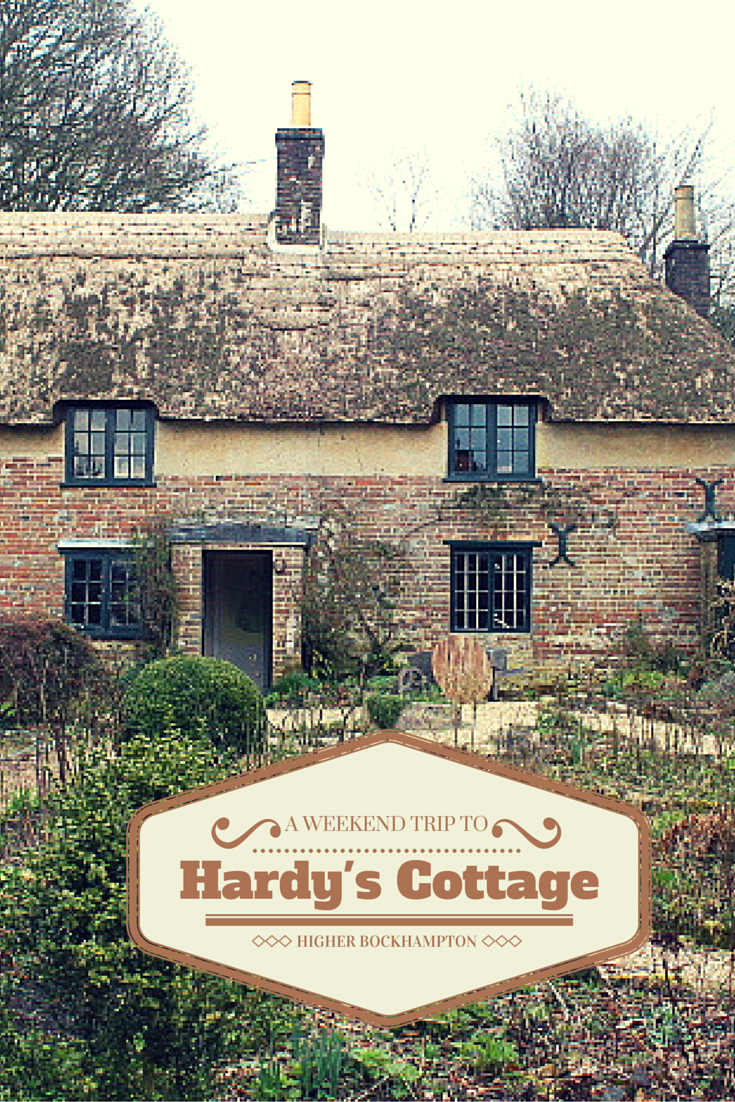

Amongst towering oaks and a collage of greens, browns and oranges, a large Dorset thatched cottage waits silently. As I approach westward, along a powdery track, the only sound that distinguishes this scene from over a century ago, is the gritty purr of an electric mower.

Although the trees are taller and the bracken and woodland are today more passable, thanks to The National Trust, the cottage still stands as Thomas Hardy would’ve drawn it – and loved it – all those years before.

It faces west, and round the back and sides high beeches, bending, hang a veil of boughs, and sweep against the roof.

Watching and waiting

Thomas Hardy spent his childhood wandering through the surrounding fields and heathland, taking note of the flowers, plants and the wildlife, whilst the grey cob face of the cottage, which was built by his great-grandfather, watched on.

Thomas’s poem, Domicilium, written about this family home by a 17-year-old Thomas, has all the natural sparkle of the author’s later genius. And the poem’s original manuscript is still on display in Hardy’s Cottage in Dorset today.

Behind, the scene is wilder. Heath and furze are everything that seems to grow and thrive upon uneven ground.

Just A Boy

It was in this thatched cottage, on a Tuesday morning in 1840, that a newborn baby boy was thrown aside, onto the uneven floor, as dead.

Today, standing in this same room with the same chestnut floorboards underfoot, I can sense the drama of that sticky June morning; with the cry of the nurse who attended Jemima Hardy (Thomas’s mother), as she realised that the infant – in fact – lived:

“Dead! Stop a minute, he’s alive enough sure.”

A World in Writing

Leaving the room Thomas Hardy was born in, thankful for the nurse that brought him into the world, I bend cautiously under the low doorway and am unbalanced for a moment by a loose floorboard.

A plaintive whine creaks out announcing my entrance into the young Thomas Hardy’s bedroom – and I can’t help but smirk at the ghosts I have scattered on my arrival.

In days gone by – long gone – my father’s mother, who is now blest with the best, would take me out to walk.

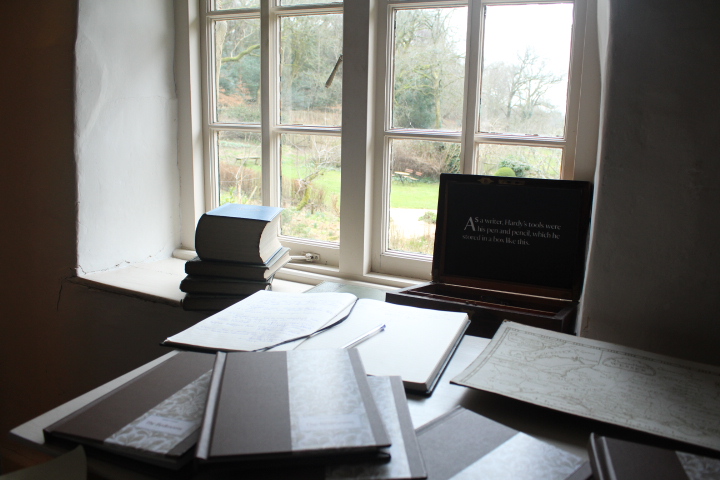

This is the room that Thomas shared with his brother Henry. It’s small and plain with only a spring bed, not the original I assume, and a wooden, padlocked chest.

The window seat, where Thomas used to sit and gaze at the Wessex he loved, has been newly painted white.

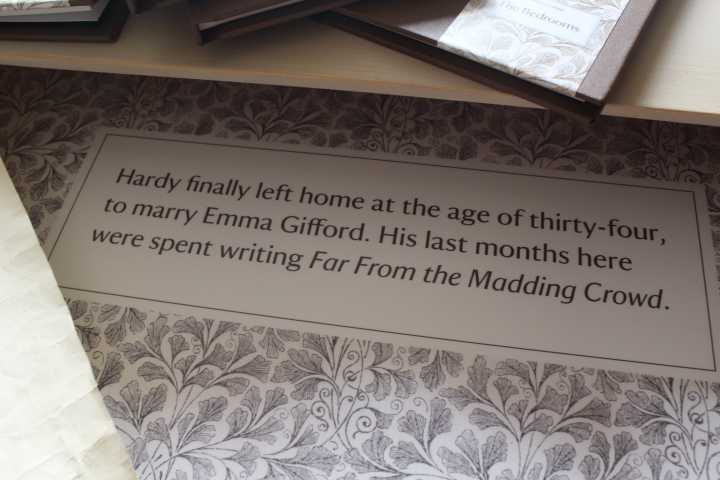

In the stillness of this room, at this seat, Hardy wrote several of his short stories and poems; he also produced Under the Greenwood Tree and Far From the Madding Crowd in here – and stayed sleeping in the room until he was 34.

Snakes and efts swarmed in the summer days, and nightly bats would fly about our bedrooms.

Farewell, not goodbye

As I leave, I can’t help but notice how the walls of this room bulge outwards; fat with secrets, no doubt, from Thomas’s younger years.

Sadly, they’ll never give up their stories: we’ll never know what Thomas and Henry chatted about as they fell asleep at night, or whether their dreams were peaceful. We can only guess – and hope they were.

Heathcroppers lived on the hills, and were our only friends;

Closing the door softly to Hardy’s Cottage, I whisper ‘goodbye’ into the space behind me – my mind fixed on my next Hardy destination, Stinsford.

Not knowing when I will return again to Hardy’s Cottage, I look around once more at the house so still and alone. For a moment, I think I see something stir in Hardy’s room; but it is just a visitor – who, like me, is looking for a man who left us all so many years before.

Where: Hardy’s Cottage, Higher Bockhampton, Dorchester, Dorset DT2 8QJ

Opening Times: Please see National Trust details here.

Leave a Reply